The mathematics of the annual testing for compliance with the rules requiring qualified plans to demonstrate nondiscrimination are spread though several sections of the tax law, rendering the calculations needed somewhat opaque. This note attempts to summarize some of the calculations so that plan sponsors might feel better empowered to assess the effect on compliance of both current and anticipated plan features.

Among the many compliance tests that qualified plans must meet in order to retain their qualified status are nondiscrimination tests which assure that the benefits of tax-deferred compensation do not accrue disproportionately to highly compensated employees (HCEs). There are several tests within this regime, but two of the more important tests, for our purposes, are the annual Actual Deferred Percentage (ADP) and Actual Contribution Percentage (ACP) calculations. While ADP considers only employee deferrals, ACP also includes employer contributions. Plan sponsors of non-exempt plans must conduct both tests, whether or not their results match.

The purpose of 401(k) nondiscrimination tests is to ensure that all employees are benefitting from plan participation. Otherwise, those who own the company and Highly Compensated Employees (HCEs) would stand to benefit disproportionately from being able to defer their income for tax purposes over Non-Highly Compensated Employees (NHCEs). Because, for example, a plan to increase the share of compensation that only HCEs may defer could cause a non-exempt plan to fail one or more nondiscrimination tests, thereby exposing the plan sponsor to penalties and possible loss of the qualified status of the plan, it is worth considering the calculations used in the ADP and ACP tests and how those calculations might be affected by adding the feature of increased deferral rights for HCEs.

For purposes of this testing, an HCE is an individual who either:

- Owned more than 5% of the interest in the business at any time during the year or the preceding year, regardless of how much compensation that person earned or received, or

- For the preceding year, received compensation from the business of more than$125,000 (if the preceding year is 2019 and $130,000 if the preceding year is 2020), and, if the employer so chooses, was in the top 20% of employees when ranked by compensation.

One of the qualifications a plan must meet to be or remain a “qualified plan” within the meaning of Code Section 401 is that it not discriminate in favor of highly compensated employees. This condition is described at §401(a)(4):[[

(4) if the contributions or benefits provided under the plan do not discriminate in favor of highly compensated employees (within the meaning of section 414(q)). For purposes of this paragraph, there shall be excluded from consideration employees described in section 410(b)(3)(A) and (C) [providing definitions for, respectively, the “year of service” and “hours of service” generally allowed as conditions for vesting]

Actual Deferral Percentage – 26 C.F.R. §1.401(k) -2

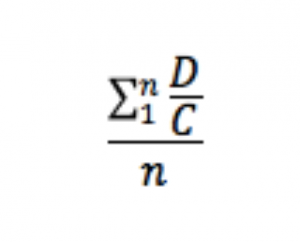

The ADP test calls for employers to compare the average annual deferral rates of HCEs and NHCEs. This test excludes employer matching and measures only employee deferrals. See, Reg. §1.401(k)-2. The ADP test also measures employee compensation only in cash and stocks. Health insurance and other fringe benefits are excluded. The employer (usually the plan administrator handles this tax, but the employer is responsible). This equation is used, separately, for both HCEs and NHCEs:

Where

n= total number of either HCEs or NHCEs

D= total employee deferrals, both pretax and Roth, for each employee

C=each employee’s total annual compensation

Actual Contribution Percentage – 26 C.F.R. §1.401(m) -2

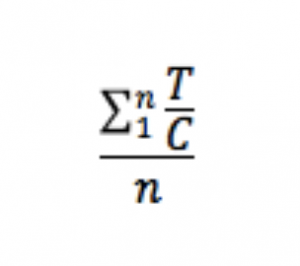

The ACP test follows a similar patter but uses different variables. This test also measures HCE and NHCE results separately:

Where

n=total number of either HCE or NHCEs

T=total of each employee’s deferrals, after tax contributions, and employer matching

C=each employee’s total annual compensation

The largest difference between the two is that the ADP test compares relative deferrals among HCEs and NHCEs but the ACP test compares the contributions of both groups that include employer matching.

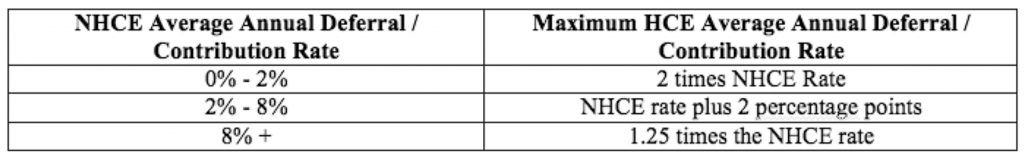

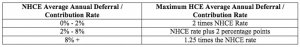

The employer then compares the test outcomes to this table:

A plan must pass both tests or the employer must take prescribed corrective action. That corrective action is not within the scope of this memo.

Using these equations, an employer can calculate its plan’s compliance at given HCE deferral rates and evaluate the effect on compliance with the nondiscrimination rules.

To be sure, the compliance tests for qualified plans are numerous, and these notes do not address the many nuances and exceptions to nondiscrimination testing. Rather, I seek here to pull back the curtain on but two often baffling, and always important, tests for qualified plans.

These notes discuss general principles only and are not intended as tax or legal advice. The reader is encouraged to discuss his or her specific circumstances with a qualified practitioner before taking any action.