Charitable organizations and their donors should be aware that the $300 deduction made available under the CARES Act expires at the end of 2020. Because this addition to the standard deduction has had such an appreciable and positive effect on charitable donations so far this year, eligible organizations might timely remind potential donors of this opportunity to support their missions.

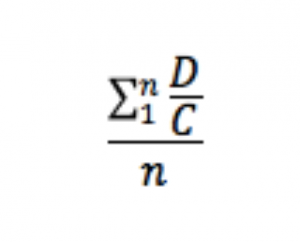

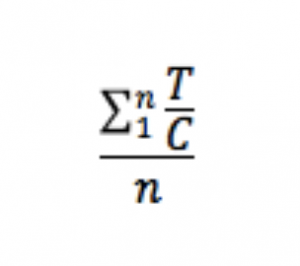

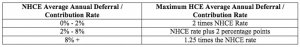

The data suggest that many donors, particularly smaller donors, have increased giving in 2020 because of the provision in the CARES Act, P.L. 116-136,1 which provides a $300 above the line charitable deduction to taxpayers who use the standard deduction and do not itemize. 2 While first quarter donations of less than $250 were up 5.8% year on year in the first quarter of 2020, they rose 19.2% at the end of the first half of the year, strongly indicating that the CARES Act, which went into effect on March 27, incented smaller donors substantially more than larger donors. Figure 1 illustrates the first quarter and first half donor data.

| < $250 | $250-$999 | ≥$1,000 | |

| Q1 2020 | + 5.8% | -2.2% | -7.4% |

| Q1 & Q2 2020 | +19.2% | +8.1% | +6.4% |

These data further suggest that small donors would increase their giving were the ceiling for qualified charitable contributions to be raised.

Nearly nine out of ten taxpayers now take the standard deduction and no longer itemize since the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, P.L. 115-97 increased the standard deduction, nearly doubled the standard deduction, and eliminated or restricted many itemized deductions for years 2018 through 2025.

The deductibility of qualified charitable contributions may be further limited by each donor’s circumstances and they should be advised to consult with their professional advisors. Organizations which receive donations of $250 or more from any donor in a calendar year are obliged to provide that donor timely written acknowledgment of the donation that complies with Reg. §§ 1.170A-16(b).

These notes are provided to illustrate general principles only. They are not legal or tax advice. The reader is cautioned to discuss his or her specific circumstances with a qualified professional before taking any action.

__________

1. Fundraising Report January 1, 2020- June 30, 2020, Association of Fundraising Professionals Foundation for Philanthropy [downloadable from my server here until December 20, 2020]

2. See, §2204 of the CARES Act, referring to donations made under this provision as “qualified charitable contributions.” §2205(a)(3)(A)(i) of the Act further limits the deduction to contributions “paid in cash during calendar year 2020 to an organization described in section 170(b)(1)(A) of such Code.”